16 Troubleshooting

So far, we haven’t talked much about what happens behind the scenes when you run quarto render.

In this chapter, you’ll learn more about what Quarto does under the hood, so you can troubleshoot problems when they occur.

16.1 What does Quarto do?

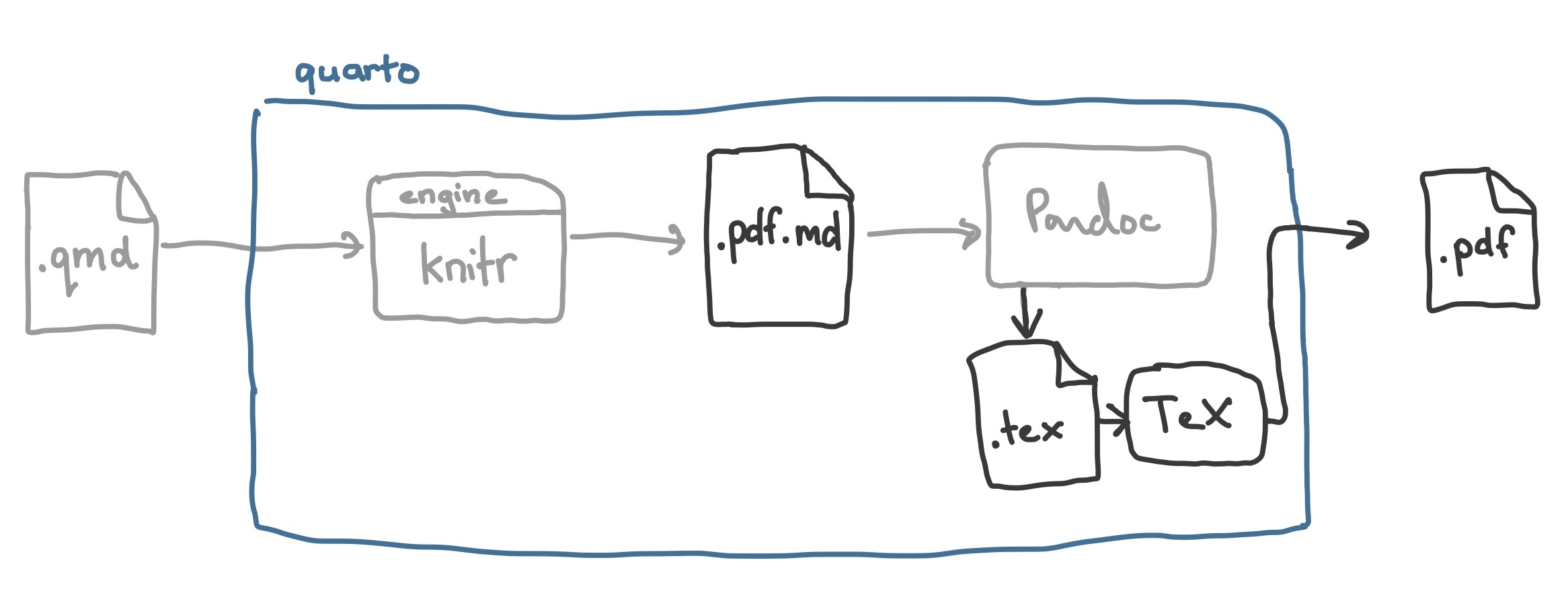

At a high level, rendering a Quarto document involves two steps:

Code execution via the computational engine (

knitr,jupyter, orjulia): The computational engine executes all the code cells in the source document and replaces the cells with static Markdown content containing the results. The result is a Markdown file (.md).Format conversion via Pandoc: The Markdown file generated in the previous step is passed to Pandoc which converts from Markdown to the required output format.

To help you understand this process, you’ll follow a series of documents through these steps. You’ll start with a document that targets the HTML format and has only R code chunks, then see how the process alters for a document with Python code cells and a document that targets PDF.

16.2 An HTML document with R code cells

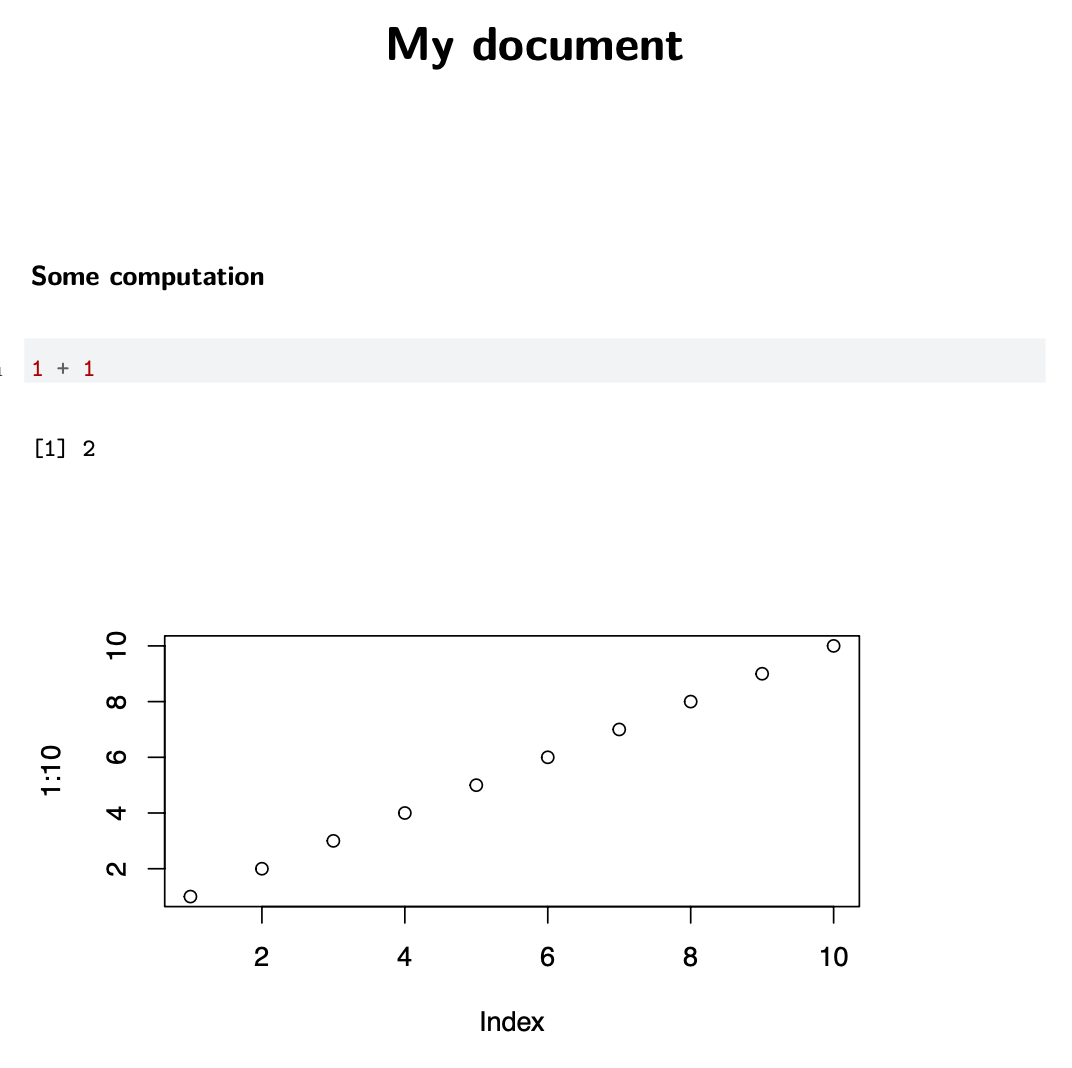

The document in Snippet 16.1, html-r.qmd, is a Quarto document that targets the HTML format and contains two R code cells.

html-r.qmd is a Quarto document with R code cells and placeholder text, targeting HTML output.

---

title: My document

format: html

---

## Some computation

```{r}

#| code-line-numbers: true

1 + 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

plot(1:10)

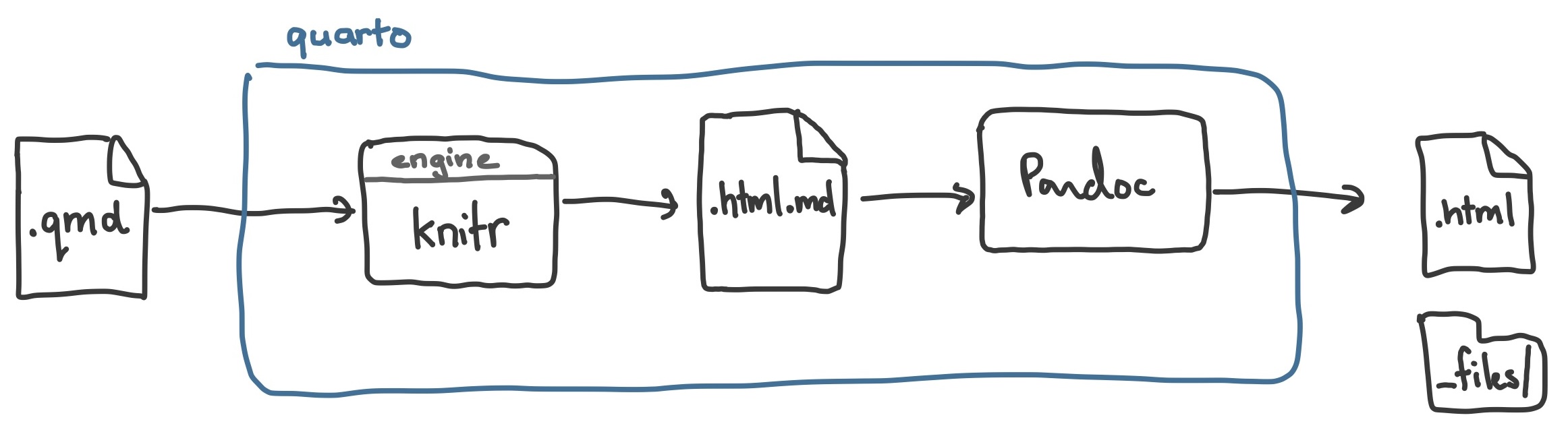

```The process this file undergoes when you call quarto render is illustrated in Figure 16.1. You’ll dive into the details of each step below.

quarto render process for html-r.qmd

16.2.1 Before the computational engine

Before anything else, Quarto parses your file to extract the document header and code cells. Quarto determines the set of formats that need to be rendered and select the appropriate computational engine.

Include shortcodes are also resolved at this stage because they may contribute code cells to the document.

It’s at this stage you’ll get errors about malformed YAML in your document header— these start with ERROR: YAMLError:. You can learn more about common YAML issues in Chapter 15.

Each input file is only ever run through one computational engine: knitr, jupyter, or julia. 1 With no additional information from the metadata (e.g. none of engine, jupyter, nor knitr), Quarto will choose the engine based on the file extension and the language of executable code cells in the document.

For .qmd documents, Quarto will use:

knitr, if there are any{r}code cells.jupyter, if there are any executable code cells other than{r}. The Jupyter kernel will be chosen based on the first executable code cell.The

markdownengine, equivalent to using no computational engine, if there are no executable cells.

For html-r.qmd, HTML is the only format specified in the header, and assuming no --to argument was specified in the quarto render call, Quarto will know to target it. Since, html-r.qmd contains executable R code cells (and doesn’t specify engine otherwise) Quarto selects the knitr engine.

16.2.2 Computational engine

The selected computational engine is informed of the target format. It runs the executable code cells and any inline code expressions, replacing them with appropriate Markdown, abiding by the execution options specified in the metadata and code cells. The result is a Markdown file. You can examine this Markdown file by adding keep-md to your document metadata:

---

title: My document

keep-md: true

---Snippet 16.2 shows the resulting Markdown file for html-r.qmd. Notice that the document header and Markdown content have passed through unchanged. However, there are now no {r} code cells. These are replaced by Markdown, albeit with some special classes attached.

html-r.html.md the intermediate Markdown created after passing html-r.qmd through the knitr engine.

---

title: My document

format: html

---

## Some computation

::: {.cell}

```{.r .cell-code code-line-numbers="true"}

1 + 1

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-stdout}

```

[1] 2

```

:::

:::

::: {.cell}

::: {.cell-output-display}

{width=672}

:::

:::For example, the executable code cell that does some addition in Snippet 16.2 (a) is replaced in Snippet 16.2 (b) by a fenced div with the class .cell that contains:

A non-executable code cell

{.r}with class.cell-codeand the attributecode-line-numbers="true"that contains the code — this is the “echo”.A fenced div with classes

.cell-outputand.cell-output-stdoutthat contains a code cell with the result.

```{r}

#| code-line-numbers: true

1 + 1

``` knitr engine.

::: {.cell}

```{.r .cell-code code-line-numbers="true"}

1 + 1

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-stdout}

```

[1] 2

```

:::

:::html-r.qmd before and after being processed by the knitr computational engine.

You can see a similar transformation has occurred on the code cell creating a plot. However, now there is no “echo”, because the code cell included the option echo: false, and the output is an image stored in html-r_files/figure-html/.

The name of the intermediate file, html-r.html.md, includes the format, .html because the engine is run separately for each format. The Markdown output and supporting files are format specific. You’ll see an example of this in Section 16.4.

If you receive an error from the computational engine, you won’t get the get the intermediate Markdown file. Common errors that arise during execution by the computational engine are discussed in Section 16.7.2.

16.2.3 Pandoc

The Markdown file is passed along to Pandoc2 for conversion into the desired output format. Pandoc’s role in rendering provides many of the features for authoring Quarto documents. For example, the syntax you learned for headings, quotations, lists, tables, links and footnotes is the syntax defined by Pandoc (see Pandoc’s Markdown on the Pandoc documentation site). Other more complicated features, like the default handling of citations with citeproc, also come directly from Pandoc (see Citations on the Pandoc documentation site).

However, Quarto adds many of its own features beyond those available in Pandoc. These are added via an established mechanism for customizing Pandoc output: filters. When Pandoc reads an input file, it translates it into an abstract representation known as an abstract syntax tree. Filters are functions that operate on this abstract syntax tree, transforming it before it is written out to the desired format. Cross-references, shortcodes3, and code annotation are examples of features that Quarto adds via filters.

For documents targeting the HTML format the output file returned to you is the output returned from Pandoc. An excerpt from html-r.html, the HTML file returned from quarto render html-r.qmd is shown in Snippet 16.3. There are more than 100 lines of HTML prior to this excerpt, but we’ve excluded that code here to focus on the part of the document that reflects our content.

html-r.html—the final output file from rendering html-r.qmd

<section id="some-computation" class="level2">

<h2 class="anchored" data-anchor-id="some-computation">Some computation</h2>

<div class="cell">

<div class="sourceCode cell-code" id="cb1"><pre class="sourceCode numberSource r number-lines code-with-copy"><code class="sourceCode r"><span id="cb1-1"><a href="#cb1-1"></a><span class="dv">1</span> <span class="sc">+</span> <span class="dv">1</span></span></code><button title="Copy to Clipboard" class="code-copy-button"><i class="bi"></i></button></pre></div>

<div class="cell-output cell-output-stdout">

<pre><code>[1] 2</code></pre>

</div>

</div>

<div class="cell">

<div class="cell-output-display">

<div>

<figure class="figure">

<p><img src="html-r_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-2-1.png" class="img-fluid figure-img" width="672"></p>

</figure>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</section>The Markdown is now converted to HTML. For example, the Markdown section heading ## A computation is represented by a <h2> heading:

<h2 class="anchored" data-anchor-id="some-computation">Some computation</h2>The fenced divs have been literally converted to <div> elements, and code blocks to <pre> elements.

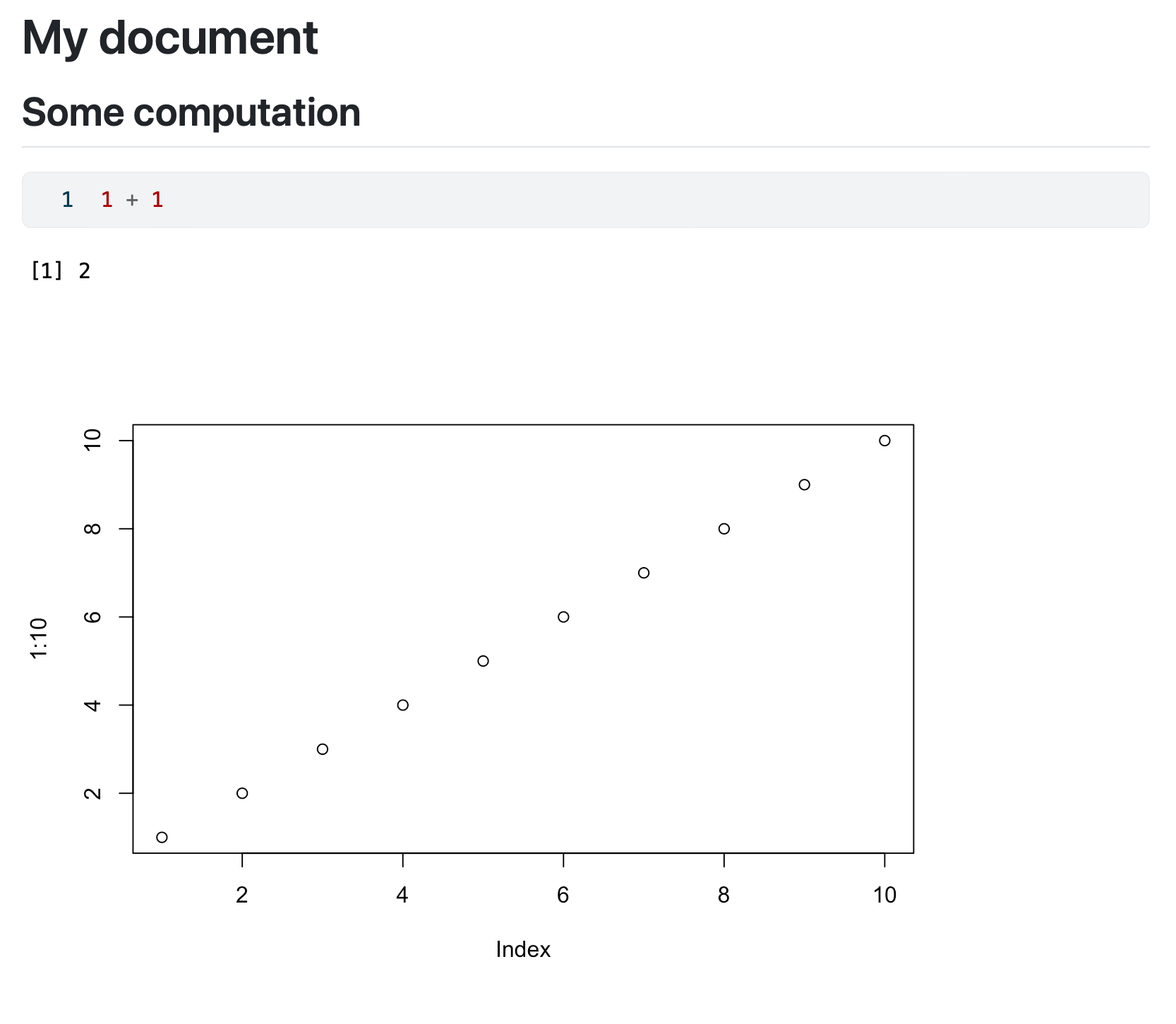

This HTML file requires some additional resources for a browser to correctly render it, but Quarto provides them all in html-r_files/. When you open html-r.qmd in a browser you’ll see the final rendered document (Figure 16.3).

quarto render html-r.qmd

Converting the Markdown to HTML commands isn’t enough to have a complete HTML document. The converted content is pasted into a template that adds the boilerplate required to form a complete document. Quarto has default templates it uses unless otherwise specified. You’ll learn more about templates and customizing them in Section 17.4.

16.2.4 Monitoring the process on the command line

You can also see this process in the messages Quarto prints as it runs. These messages are generated when you run quarto render or quarto preview, but you may have missed them because they scroll quickly past or are hidden in a pane in your IDE. In Figure 16.4, you can see the messages Quarto prints in the Terminal during a successful render of html-r.qmd.

Knitr generates the first chunk of output as it processes the document and runs the code in the three (unnamed) chunks. The remaining output gives some information on the settings being passed along to pandoc.

Terminal

1$ quarto render html-r.qmd

2processing file: html-r.qmd

1/5

2/5 [unnamed-chunk-1]

3/5

4/5 [unnamed-chunk-2]

5/5

output file: html-r.knit.md

3pandoc

to: html

output-file: html-r.html

standalone: true

section-divs: true

html-math-method: mathjax

wrap: none

default-image-extension: png

metadata

document-css: false

link-citations: true

date-format: long

lang: en

title: My document

4Output created: html-r.html- 1

- Quarto starts working, you may hang here for awhile as Quarto parses what it needs to plan its work.

- 2

- Knitr executes the code cells

- 3

- The information passed along to Pandoc

- 4

- A final message from Quarto indicating success

quarto render when run on html-r.qmd.

16.3 An HTML document with Python code cells

Snippet 16.4 shows html-python.qmd, a file that is very similar to html-r.qmd except instead of R code cells, it has Python code cells.

html-python.qmd a Quarto document with Python code cells and placeholder text, targeting HTML output.

---

title: My document

format: html

---

## Some computation

```{python}

#| include: false

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

```

```{python}

#| code-line-numbers: true

1 + 1

```

```{python}

plt.plot(range(1, 11))

plt.show()

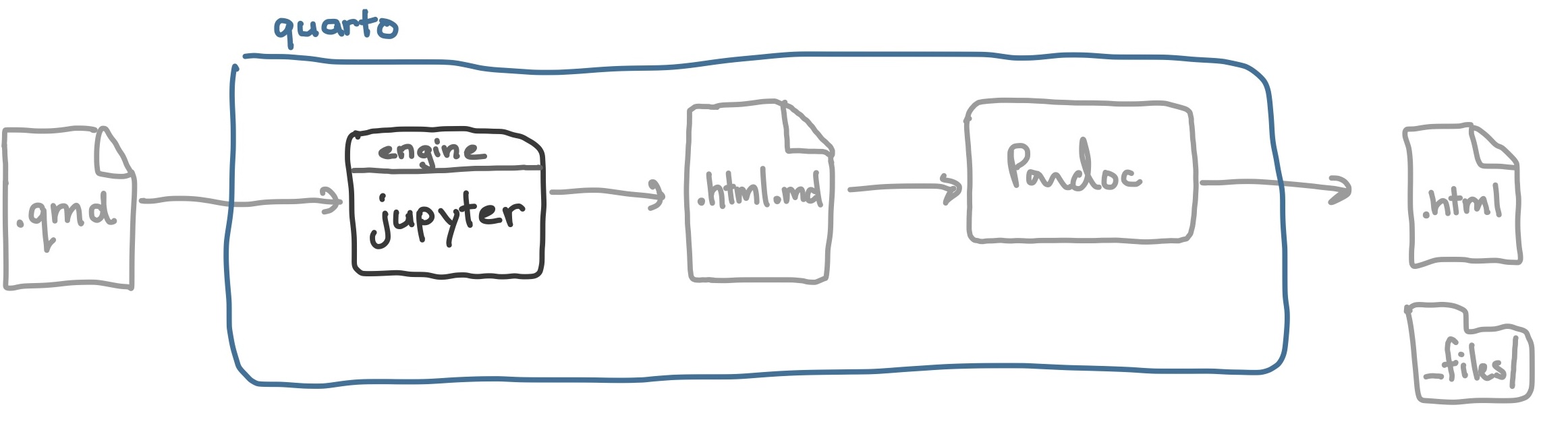

```In Figure 16.5 we show the process of rendering html-python.qmd, greying those parts that are the same as the process for html-r.qmd.

quarto render process for html-python.qmd

16.3.1 Before computational engine

Like html-r.qmd, the only format specified in the header of html-python.qmd is HTML. Unlike html-r.qmd, html-python.qmd contains only Python code cells, so Quarto will select the jupyter engine. Since the first code cell is a Python code cell, the python kernel will be selected.

16.3.2 Computational engine

Now rather than knitr, the jupyter engine is responsible for executing the code cells and replacing them with Markdown.

The intermediate file html-python.md.html is shown in Snippet 16.5. Just like when knitr processed html-r.qmd, the jupyter engine has replaced the executable code cells ({python}) with non-executable ones ({.python}), and placed the code and output in fenced divs with appropriate classes.

html-python.html.md, the intermediate Markdown created after passing html-python.qmd through the jupyter engine.

---

title: My document

format: html

---

## Some computation

::: {#05056103 .cell execution_count=2}

``` {.python .cell-code code-line-numbers="true"}

1 + 1

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-display execution_count=2}

```

2

```

:::

:::

::: {#13ea8596 .cell execution_count=3}

``` {.python .cell-code}

plt.plot(range(1, 11))

plt.show()

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-display}

{width=566 height=411}

:::

:::Functionally, the different engines should produce very similar output given the same code, but they do have their own idiosyncrasies. For instance, you can see the jupyter engine has added unique code cell identifiers and an execution_count attribute to the code cells.

16.3.3 Pandoc

Nothing changes in the Pandoc step. The intermediate Markdown is passed to Pandoc with the exact same settings as in the html-r.qmd example.

16.3.4 Monitoring the process on the command line

You can also see the similarities in the process through messages Quarto prints on the command line (Figure 16.6). The only difference is where the computational engine runs.

Terminal

1$ quarto render html-python.qmd

2Starting python3 kernel...Done

Executing 'html-python.quarto_ipynb'

Cell 1/3: ''...Done

Cell 2/3: ''...Done

Cell 3/3: ''...Done

3pandoc

to: html

output-file: html-python.html

standalone: true

section-divs: true

html-math-method: mathjax

wrap: none

default-image-extension: png

toc: true

metadata

document-css: false

link-citations: true

date-format: long

lang: en

title: My document

4Output created: html-python.html- 1

- Quarto starts working

- 2

- Jupyter executes the code cells

- 3

- The information passed along to Pandoc

- 4

- A final message from Quarto indicating success

quarto render when run on html-python.qmd.

16.4 A PDF document with R code cells

Now consider the document pdf-r.qmd shown in Snippet 16.6. This document is identical to html-r.qmd except instead of targeting the HTML format, it targets PDF.

pdf-r.qmd a Quarto document with R code cells that targets the PDF format.

---

title: My document

format: pdf

---

## Some computation

```{r}

#| code-line-numbers: true

1 + 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

plot(1:10)

```Figure 16.7 shows the process of rendering pdf-r.qmd, again greying those parts that are the same as the process for html-r.qmd.

quarto render process for pdf-r.qmd

16.4.1 Before the computational engine

Quarto identifies the target format as PDF, and selects the knitr engine.

16.4.2 Computational engine

There isn’t any difference in how the computational engine, knitr, is run compared to when the target format was HTML, but the engine is aware the target format is now PDF. This means the the engine can tailor output to the target format. In Snippet 16.7 you can see the intermediate Markdown file that is produced.

pdf-r.pdf.md the intermediate Markdown file after the knitr engine has exectuted the code in pdf-r.qmd

---

title: My document

format: pdf

---

## Some computation

::: {.cell}

```{.r .cell-code code-line-numbers="true"}

1 + 1

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-stdout}

```

[1] 2

```

:::

:::

::: {.cell}

::: {.cell-output-display}

:::

:::It is mostly identical to that produced when the target format was HTML, but there are some differences. In particular, compare the Markdown used to include the plot (Figure 16.8).

{width=672}{fig-pos='H'}knitr engine for when targeting (a) HTML, and (b) PDF.

When targeting PDF there is a LaTeX specific attribute added, fig-pos='H', and the file included is a PDF, compared to a PNG.

16.4.3 Pandoc

When the target format was HTML, Pandoc handled the conversion, and Quarto returned the HTML document directly from Pandoc. When the target format is PDF, Pandoc only converts to LaTeX, and Quarto handles the remaining conversion from LaTeX to PDF.

This means Pandoc is called on pdf-r.pdf.md in the same way as on pdf-r.html.md, but with the format set to latex. You can examine the .tex file Pandoc returns by setting keep-tex to true:

---

title: My document

format: pdf

keep-tex: true

---An excerpt of the resulting .tex file is shown in Snippet 16.8. Above this excerpt is almost 200 lines of other TeX commands setting up the document.

pdf-r.tex, the TeX file created after passing pdf-r.pdf.md through Pandoc.

\subsection{Some computation}\label{some-computation}

\begin{Shaded}

\begin{Highlighting}[numbers=left,,]

\DecValTok{1} \SpecialCharTok{+} \DecValTok{1}

\end{Highlighting}

\end{Shaded}

\begin{verbatim}

[1] 2

\end{verbatim}

\includegraphics{pdf-r_files/figure-pdf/unnamed-chunk-2-1.pdf}Now the Markdown syntax has been converted to TeX syntax: section headings are created with the TeX command \subsection, code cells use Shaded and Highlighting environments, and output uses appropriate commands like the verbatim environment for code output, and the \includegraphics command for the image file.

16.4.4 After Pandoc

There is an additional step now required—Quarto runs the .tex document through LaTeX to produce the PDF.

Quarto will look for, and use an installation of TeX. If TeX is not installed, you can install it with:

Terminal

quarto install tinytexQuarto will prefer the version installed this way over other installations.

Quarto will use the detected installation and process the .tex file as many times as needed to resolve all cross references and citations.

Figure 16.9 shows part of the PDF output that results for pdf-r.qmd.

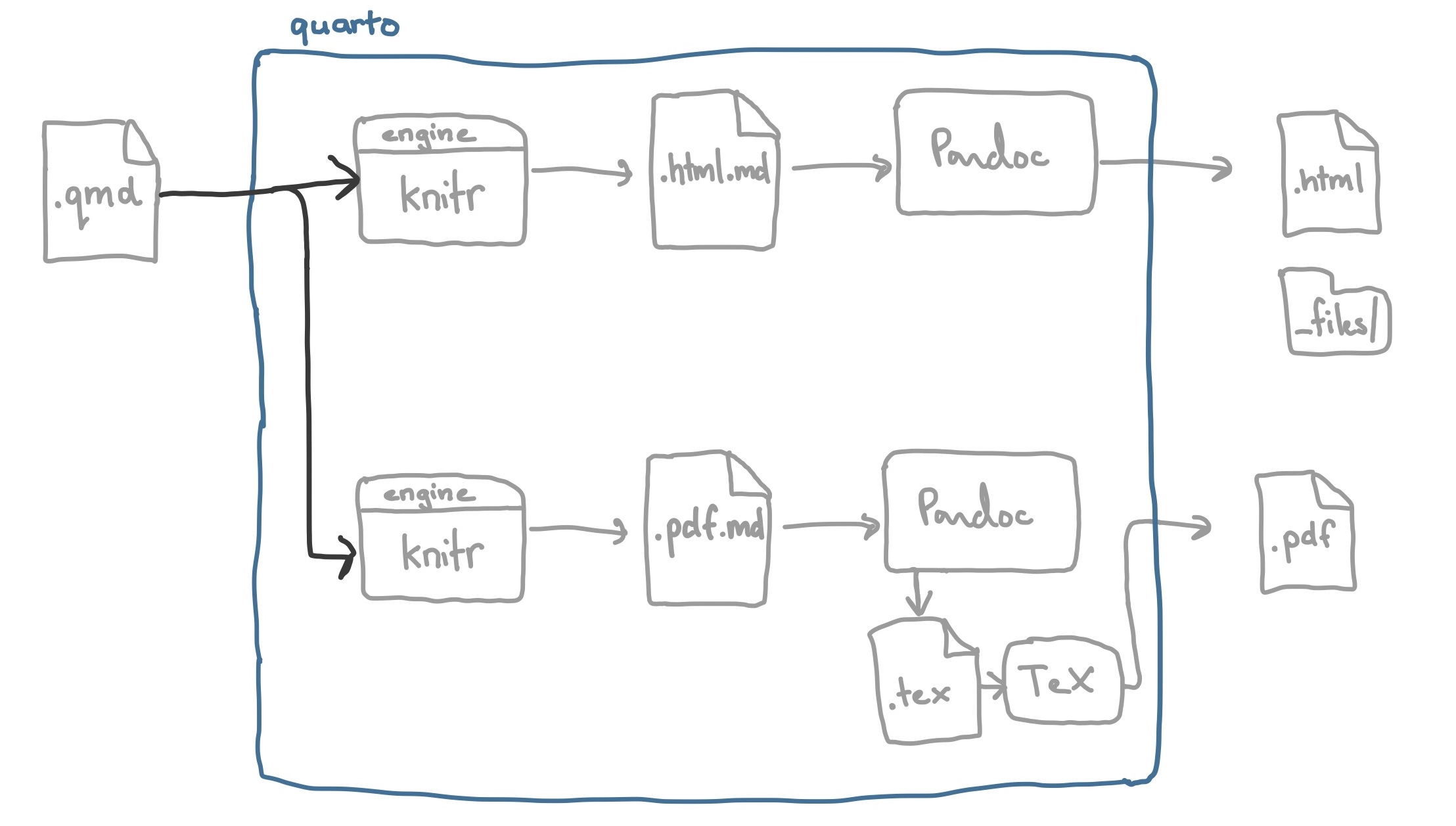

16.5 A multi-format document

You’ve seen what happens when a single format is declared. But, what if more than one is declared? For example, you might have specified both PDF and HTML in your document header:

---

format:

pdf: default

html: default

---Figure 16.10 illustrates what happens. Before the computational engine, Quarto recognizes that more than one format is a target. Each format is then generated in series and passes through the render process independently: the computational engine is run for each format; an intermediate Markdown file is generated for each format; Pandoc is run for each format; and any post-Pandoc steps are completed for each format.

16.6 Other variations

16.6.1 Other types of input file

You’ve seen the render process specifically for .qmd inputs, but Quarto accepts other types of input files. For .Rmd, .ipynb, and .md, the primary difference is that the engine is selected based on the file type: jupyter for .ipynb , but see Note 16.1; knitr for .Rmd ; and markdown for.md.

For script files (.R,.py,.jl etc.) the file is pre-processed into a .qmd file before continuing the render process as described above.

Since .ipynb files store their output alongside the source, the code cells are not executed by default when you run quarto render. To execute the cells, pass the --execute flag to quarto render:

Terminal

quarto render document.ipynb --execute16.6.2 Other target formats

Most formats are like HTML, they are simply passed along to Pandoc with the Markdown file, Pandoc handles the conversion to the target format, and Quarto does no further processing.

One exception is Typst. Typst is like PDF: Pandoc handles the conversion into the Typst format .typ, and Quarto handles the final conversion to PDF. In contrast to format: pdf where Quarto looks for an external TeX installation, for format: typst Quarto runs the Typst version provided internally with Quarto. This is equivalent to:

Terminal

quarto typst compile document.typ16.6.3 Preview vs. render

When you are working with a Quarto document, you’ll often be running quarto preview as opposed to quarto render. Think about quarto preview as a two-step process: first, run quarto render; then, serve the document. For HTML documents this means starting up a webserver, for other formats, opening some other form of viewer.

16.6.4 Rendering projects

Think about rendering a project, as rendering a folder of documents, where each one goes through the process above. Quarto often needs to do some processing before, or after (or both) rendering each document, depending on the type of project. For example, for websites Quarto needs to run through all documents to build the list of navigation items, before rendering individual pages.

Some projects may also involve freeze. When freezing a document it is the intermediate Markdown file that gets put in the freezer, effectively removing the computational engine step when the freezer is activated.

16.7 Troubleshooting

In this section, you’ll learn some tips for troubleshooting problems when they do occur.

16.7.1 Run quarto check

As you’ve seen, Quarto potentially accesses and runs many other tools. The quarto check command is a good way to check the versions of these tools and the exact ones Quarto is finding.

Run quarto check on the command line in your project after activating the relevant environment (if any):

Terminal

quarto checkFigure 16.11 shows example output from quarto check with the following highlighted:

Quarto version: Check your Quarto version against the latest release, particularly when documented features don’t seem to work for you. Before reporting a bug, you should confirm that your problem exists on the latest release, and it is good practice to also confirm that it exists on the latest pre-release version.

Internal dependencies: Tools listed here are bundled with Quarto, and you cannot link Quarto to newer versions of those tools yourself. However, knowing these versions can be useful for troubleshooting. For instance, you might be trying to use a feature of Typst that is newer than the version bundled with Quarto.

Quarto installation: The version here will match the one reported on the first line, but adds the path to Quarto. If you manage multiple installations of Quarto, you should check that you are getting the one you expect here.

Tools installed by Quarto: These tools aren’t included with Quarto but they can be installed with

quarto install. TinyTex is recommended for producing PDFs viaformat: pdf; and Chromium is required for producing versions of Mermaid and Grapviz diagrams suitable for use in PDF or DOCX. You can also check these tools by runningquarto toolswhich will inform you if they are out of date. You can update them withquarto update.LaTeX: Information about the TeX distribution Quarto will use. If you are having trouble with

format: pdfoutput, and this isn’t TinyTex, you should install TinyTex withquarto install tinytex.Python: The Python 3 interpreter discovered by Quarto—check it is the Python you expect. This is most often controlled by a virtual environment, but can also be set with the environment variable

QUARTO_PYTHON. If you are using a language other than Python with thejupyterengine, confirm that the kernel you need is listed here.R: The R interpreter discovered by Quarto—check it is the R you expect. It can be set with the environment variable

QUARTO_R.

1Quarto 1.5.56

[✓] Checking versions of quarto binary dependencies...

2 Pandoc version 3.2.0: OK

Dart Sass version 1.70.0: OK

Deno version 1.41.0: OK

Typst version 0.11.0: OK

[✓] Checking versions of quarto dependencies......OK

[✓] Checking Quarto installation......OK

3 Version: 1.5.56

Path: /Applications/quarto/bin

[✓] Checking tools....................OK

4 TinyTeX: v2024.03.13

Chromium: (not installed)

5[✓] Checking LaTeX....................OK

Using: TinyTex

Path: /xxx/Library/TinyTeX/bin/universal-darwin

Version: 2024

[✓] Checking basic markdown render....OK

6[✓] Checking Python 3 installation....OK

Version: 3.12.2

Path: /xxx/.pyenv/versions/3.12.2/bin/python3

Jupyter: 5.7.2

Kernels: julia-1.10, python3

[✓] Checking Jupyter engine render....OK

7[✓] Checking R installation...........OK

Version: 4.3.3

Path: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.3-arm64/Resources

LibPaths:

- /xxx/Library/R/arm64/4.3/library

- /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.3-arm64/Resources/library

knitr: 1.44

rmarkdown: 2.25

[✓] Checking Knitr engine render......OK- 1

- Quarto version

- 2

- Internal dependencies

- 3

- Quarto installation

- 4

- Tools installed by Quarto

- 5

- LaTeX

- 6

- Python

- 7

- R

quarto check

16.7.2 Errors from the computational engine

If your Quarto document fails to make it through the computational engine, the culprit is likely one of the following three issues:

The wrong engine is being used.

The environment Quarto sees isn’t the one you expect.

Your code has errors in it.

16.7.2.1 Wrong Engine

The heuristics Quarto uses when selecting an engine can sometimes be wrong. If you see some indication Knitr is running when you expected Jupyter, override the automatic choice by explicitly setting the engine with the engine key:

---

engine: jupyter

---If you want the julia engine, Quarto will never automatically select it; you must opt-in via the engine key.

For the purpose of choosing an engine, a code cell with the option eval: false is still considered an executable code cell, even though the code inside will not be executed. This means you might see an engine starting even if you’ve set eval: false at the document level. To avoid even starting an engine, and executing any code, you can explicitly use the markdown engine:

---

engine: markdown

---16.7.2.2 Wrong Environment

The usual symptom of Quarto not using the right environment is the failure to load packages you are sure you installed. Troubleshooting your environment is language-specific, and you should refer back to the relevant sections of Chapter 7 and Chapter 8.

16.7.2.3 Code Errors

When the code in your executable code cells generates an error, the computational engine will halt and Quarto will exit. Figure 16.12 shows an example of this for the three engines–—in all cases the code cell producing the error requests the variable x which hasn’t been defined. The output differs by engine, but you’ll generally see the engine start progressing through the cells (e.g. Cell 1/1 in Figure 16.12 (a)) then an error report native to the language of your cells (e.g. NameError: name 'x' is not defined from Python in Figure 16.12 (a)).

Executing 'python-error.quarto_ipynb'

Cell 1/1: ''...ERROR:

An error occurred while executing the following cell:

------------------

x

------------------

-------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[2], line 1

----> 1 x

NameError: name 'x' is not definedjupyter engine

processing file: r-error.qmd

1/2

2/2 [unnamed-chunk-1]

Quitting from lines 7-8 [unnamed-chunk-1] (r-error.qmd)

Error:

! object 'x' not found

Execution haltedknitr engine

Running [1/1] at line 7: x

ERROR: Julia server returned error after receiving "run" command:

Failed to run notebook: /Users/charlottewickham/Documents/posit/weekly-log/2024-09-30/julia-error.qmd

ERROR: EvaluationError: Encountered 1 error during evaluation

Error 1 of 1

@ /Users/charlottewickham/Documents/posit/weekly-log/2024-09-30/julia-error.qmd:7

UndefVarError: `x` not definedjulia engine

quarto render when there is an execution error.

If you want to show an error in your document, set the option error: true in the corresponding code cell. This will prevent the error from halting execution, and include the error message in your rendered document.

You are now in the realm of debugging your R, Python, or Julia code. The first way to make your life easier is to label your code cells:

```{r}

#| label: get-x

x

```When the engines process your code cells, they will include the label, helping you to identify which code cell caused the error quickly.

If the error isn’t obvious, run your code from top to bottom interactively in a clean session of your interpreter.

In RStudio, use the command Restart R Session and Run All Chunks.

In the Quarto extension for VS Code and Positron, use the command Quarto: Run All Cells.

16.7.3 Things that aren’t errors

Some problems don’t rise to the level of errors. You might get output from quarto render but it might not look right. In this case, a general troubleshooting process might look like:

Verify you’re working with the current release of Quarto (e.g. with

quarto check).Find an example of what you are trying to do in the documentation and verify it works. If it does work, gradually alter it to match your example, until it no longer works—you’ll either discover what you are doing wrong, or you’ll produce a minimal reproducible example.

Ask for help using your reproducible example.

16.7.4 Asking for help

If you can’t figure out the problem yourself, your next step is to ask someone. A good question includes:

- A description of your problem, including what you expected to happen and what actually happened.

- A minimal reproducible example (see Section 6.4).

- The output from

quarto check.

Some good venues to ask questions are the discussion board on the quarto-cli repository and Posit community.

16.8 Wrapping Up

We use lower-case engine names, e.g.

knitrvs. Knitr, because a computational engine is more than the tool that does the execution. For example, although the Jupyter project NBClient does the execution when the engine isjupyter, thejupyterengine also encompasses translating the.qmdto an.ipynband back again after execution—tasks that are handled by Quarto itself.↩︎Quarto includes a particular version of Pandoc. You don’t need to install or manage it separately, and it won’t interfere with any other version of Pandoc you have installed. If you ever need to run Quarto’s Pandoc, you can with

quarto pandoc.↩︎Most shortcodes are implemented as filters, but there are two exceptions

includeandembed.↩︎